Words by Songkha

Images by Mimininii

Translations by Peera Songkünnatham

[คลิกที่นี่เพื่ออ่าน เด็กๆมีความฝัน ฉบับภาษาไทย]

In 2021, a series of illustrated children’s books were flagged by the Thai Ministry of Education for “misleading” content—which is to say, unabashedly positive and unflinching depictions of contemporary anti-government protesters and other revolutionaries. After an official investigation by a working group, it was announced that three books in the series were beneficial to children, while the other five were classed as books “to be wary of.” According to the Deputy Minister of Education’s spokesperson, the books have disturbing visual content that could lead to children resorting to violence to resolve conflict:

Children don’t live in the real world. They live in a fantasy world. Children’s imagination can lead them to imitation, an issue the doctor [Suriyadeo Tripathi, a pediatrician and child rights expert consulted by the working group —trans.] is very concerned about. Children [under age 6] cannot distinguish between these things. Therefore, since the five books have inappropriate content for children, the doctor’s worry is that these books may inculcate violent feelings that may influence youth in the future.

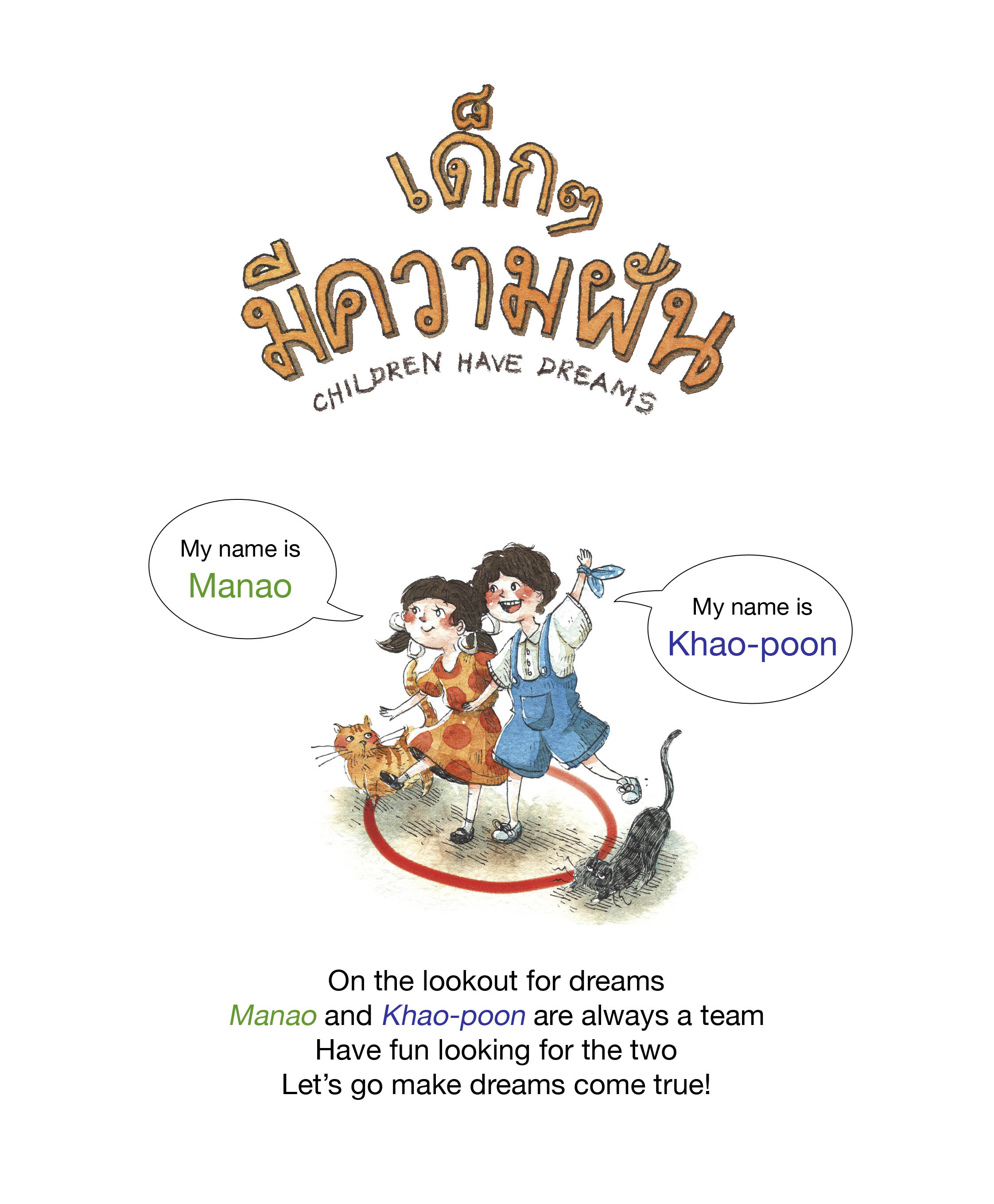

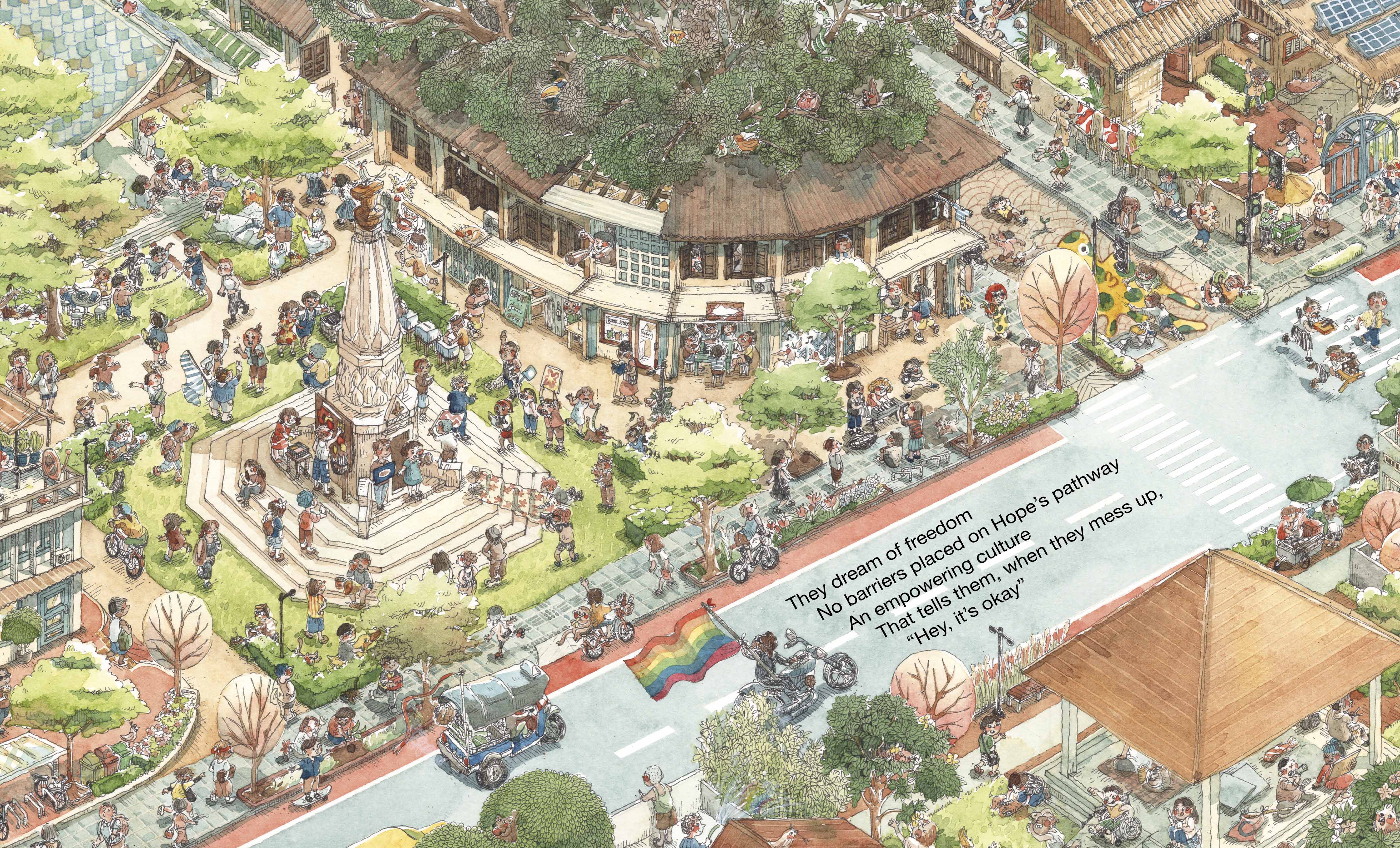

From the same series of picture books, Sanam Ratsadon presents Children Have Dreams, a certified child-friendly entry that still very much resonates thematically and visually with the 2020 protests.

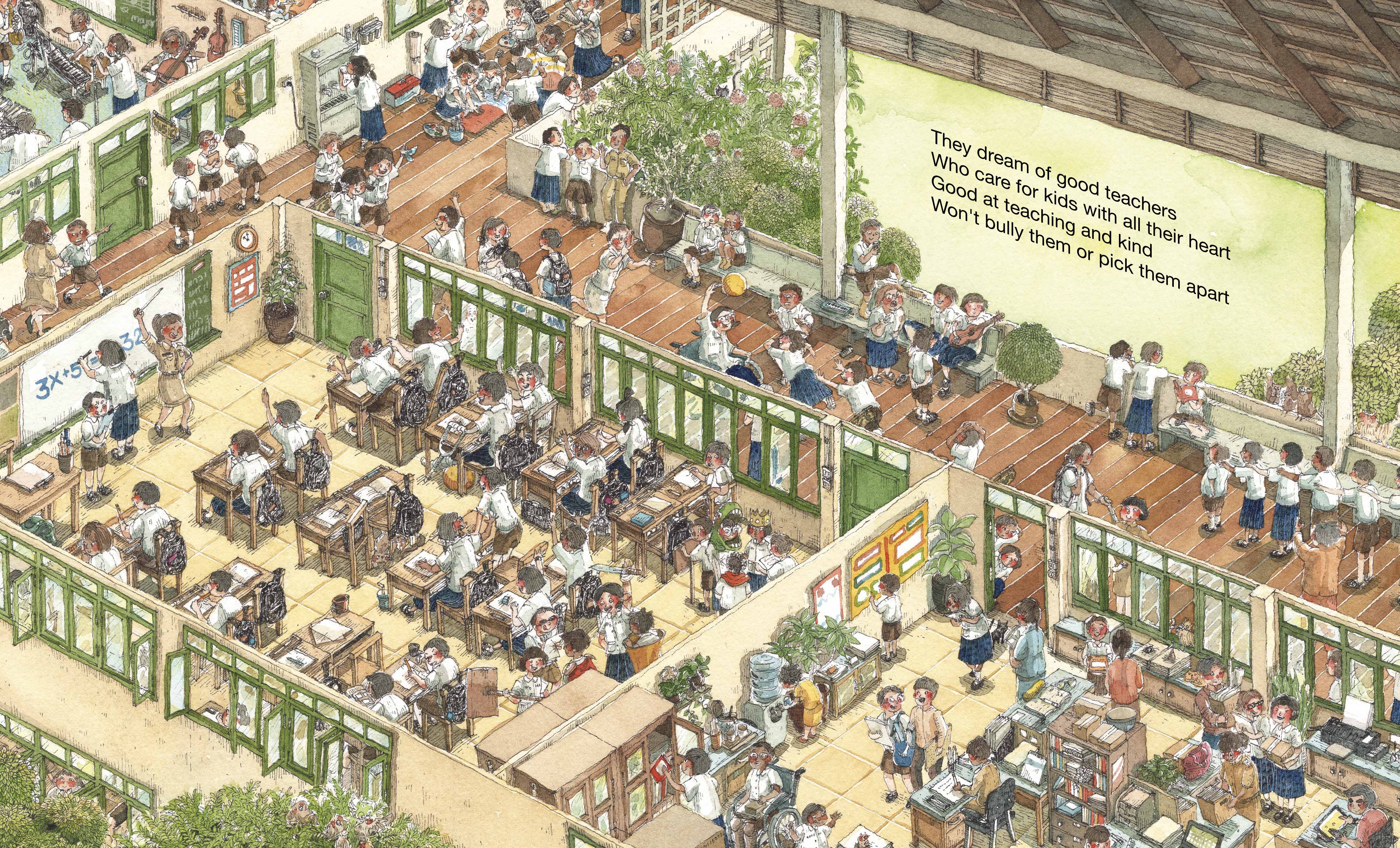

Thematically, Children Have Dreams contains both didactic and non-didactic tendencies. The title, for one, sounds like an obvious observation, until one thinks of the reality where some adults seem to need reminding that, yes, children have dreams of their own. The main text narrates those dreams in the third person, as if to describe them as is, yet they include notions that may strike the reader as adult-imposed. Then again, don’t kids these days notoriously incorporate into their everyday speech words like sit (right) and rat (the state) in defiance of authority figures in their lives? If so, then much of the apparent “dream suggestion” by the adult author can be better understood as a translation of kids’ inner hopes and dreams.

To be clear, didacticism can be a good thing. Hell, pro-democracy didacticism may precisely be what is needed in a national landscape of children’s books infiltrated by promotions of anti-democratic values. Take, for example, ใฝ่เรียน เพียรวิชา (Studious, Nanmeebooks, 2016), written by Pitiyamas Leewattanasirikul as part of a series promoting the Twelve Thai Values under General Prayut. The story follows a girl’s moral development from an irresponsible child glued to the TV to a dutifully studious one.

Studious ends in a fancy library where the girl’s eyes land, out of frame, on a portrait of someone beautiful. Who? The final page spoils it:

The teacher says,

That is Phra Thep;

Like a teacher,

She gives knowledge

For all of you.

The Reader Princess,

Weaver of Works:

We the People

Humbly revere.

[ครูบอกพระเทพฯ ท่านเปรียบดั่งครู

ประทานความรู้ เพื่อหนูทุกคน

เจ้าฟ้านักอ่าน ทรงสานนิพนธ์

พวกเราปวงชน น้อมตนเทิดทูน]

To appreciate how deep anti-democratic values run in this uniquely Thai plot twist, juxtapose it with Children Have Dreams, where

They dream that adults

Respect their independent mind

Won’t walk all over them

For being a descendent or a child

[ฝันให้พ่อแม่ผู้ใหญ่

รัก ใส่ใจ เคารพความคิด

เข้าใจ ไม่ล้ำสิทธิ์

คนตัวนิดที่เป็นลูกหลาน]

And the contrast cannot be starker. One takes book knowledge to be a gift bestowed upon the child by social superiors; the other treats a child’s mind as personal property not to be infringed upon. One infantilizes the populace by telling us to admire a bigly brilliant princess; the other has the audacity to posit that small children can be on the receiving end of respect. One reinforces seniority with enlightened royalism; the other levels it.

Ultimately, whether a book is didactic or not, and whether it lends itself to noobish imitation or noble emulation, matters less than the way it’s read. A review of Children Have Dreams models how a children’s book might be read most fruitfully:

On each and every page there’s a knot of questions for my daughter to discuss with me. Why should it be this way? Why should you want it to be this way? […] Another aspect that my kid likes is the beautiful illustrations full of details for her to examine. No boredom at all even after multiple read throughs.

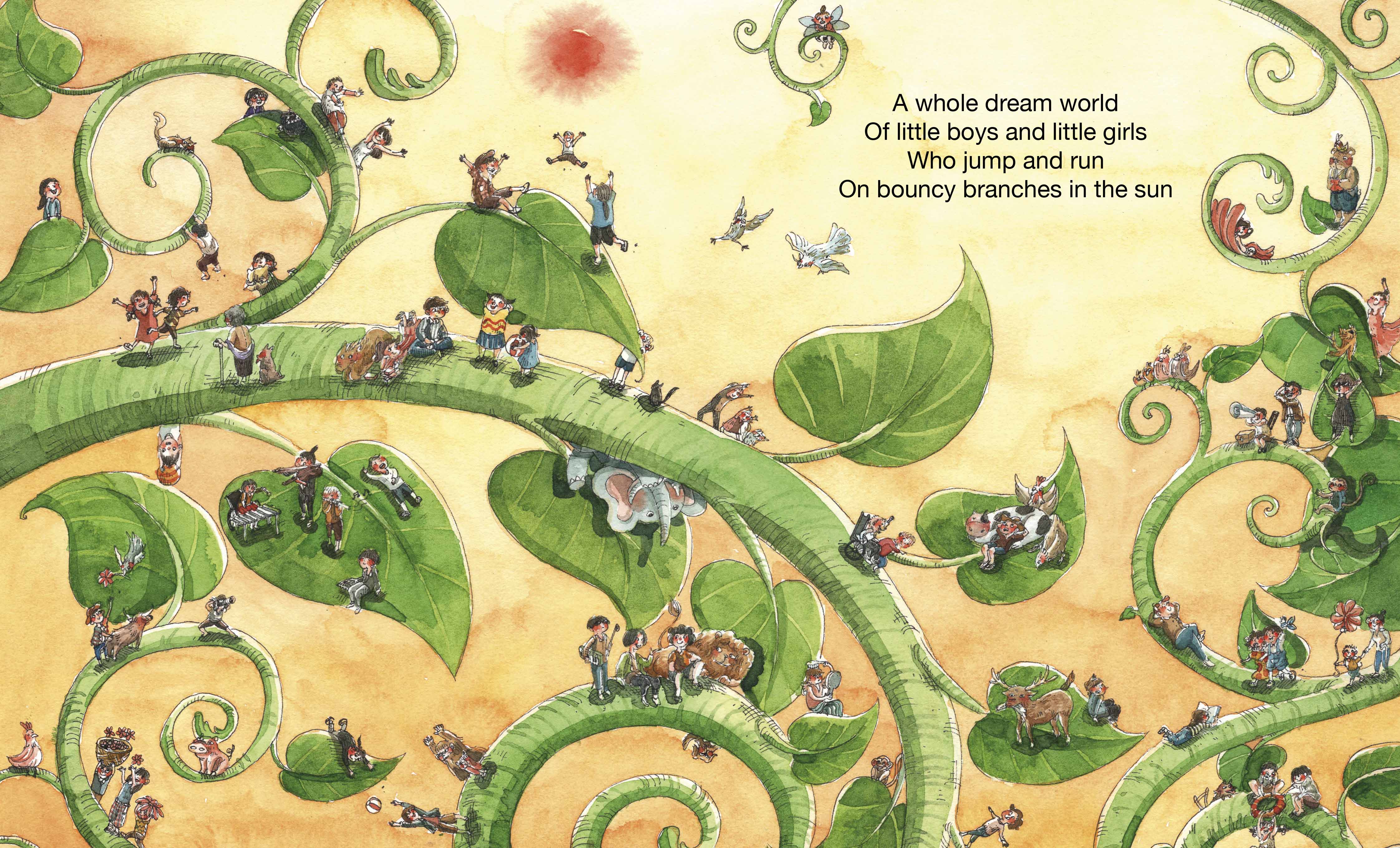

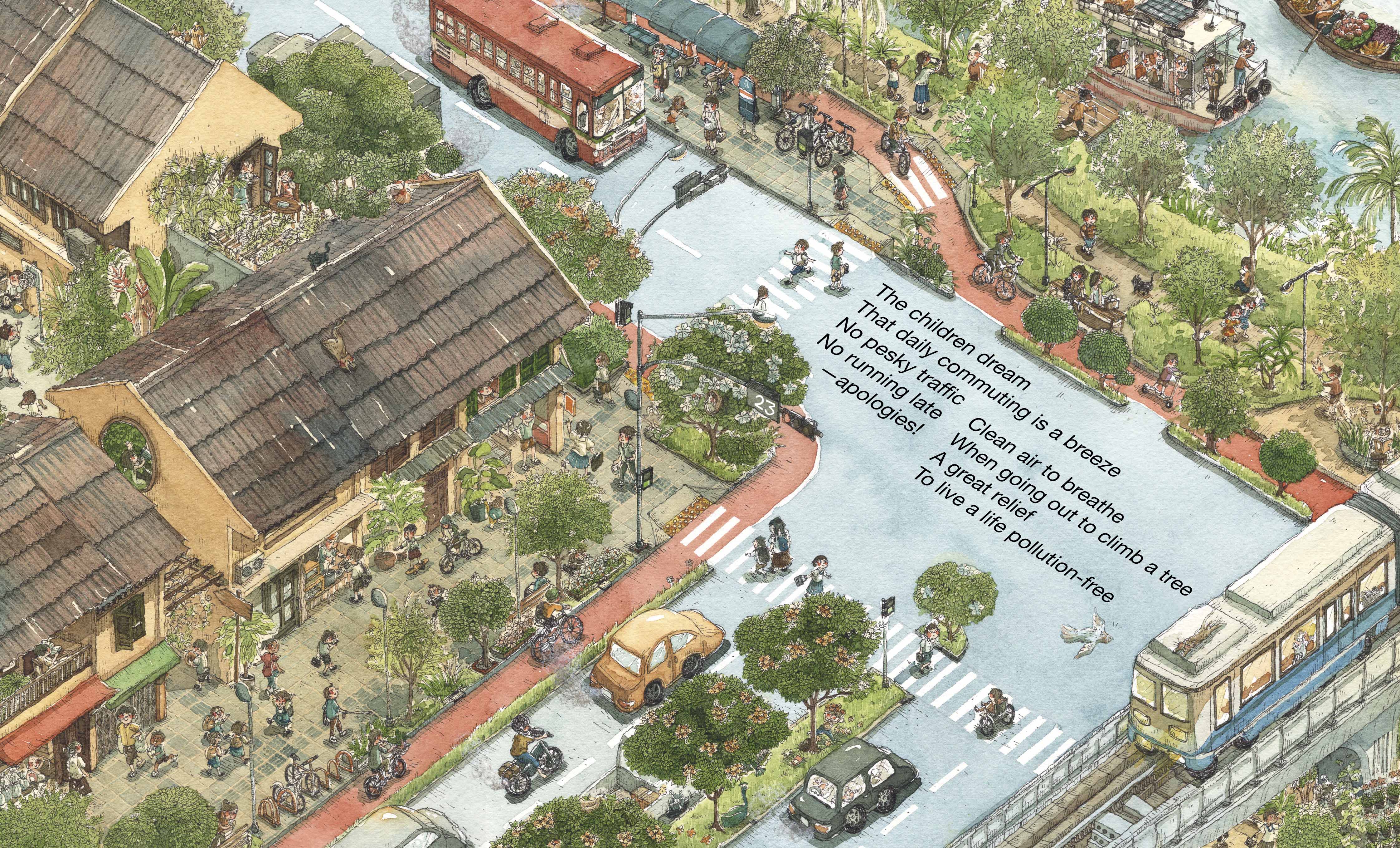

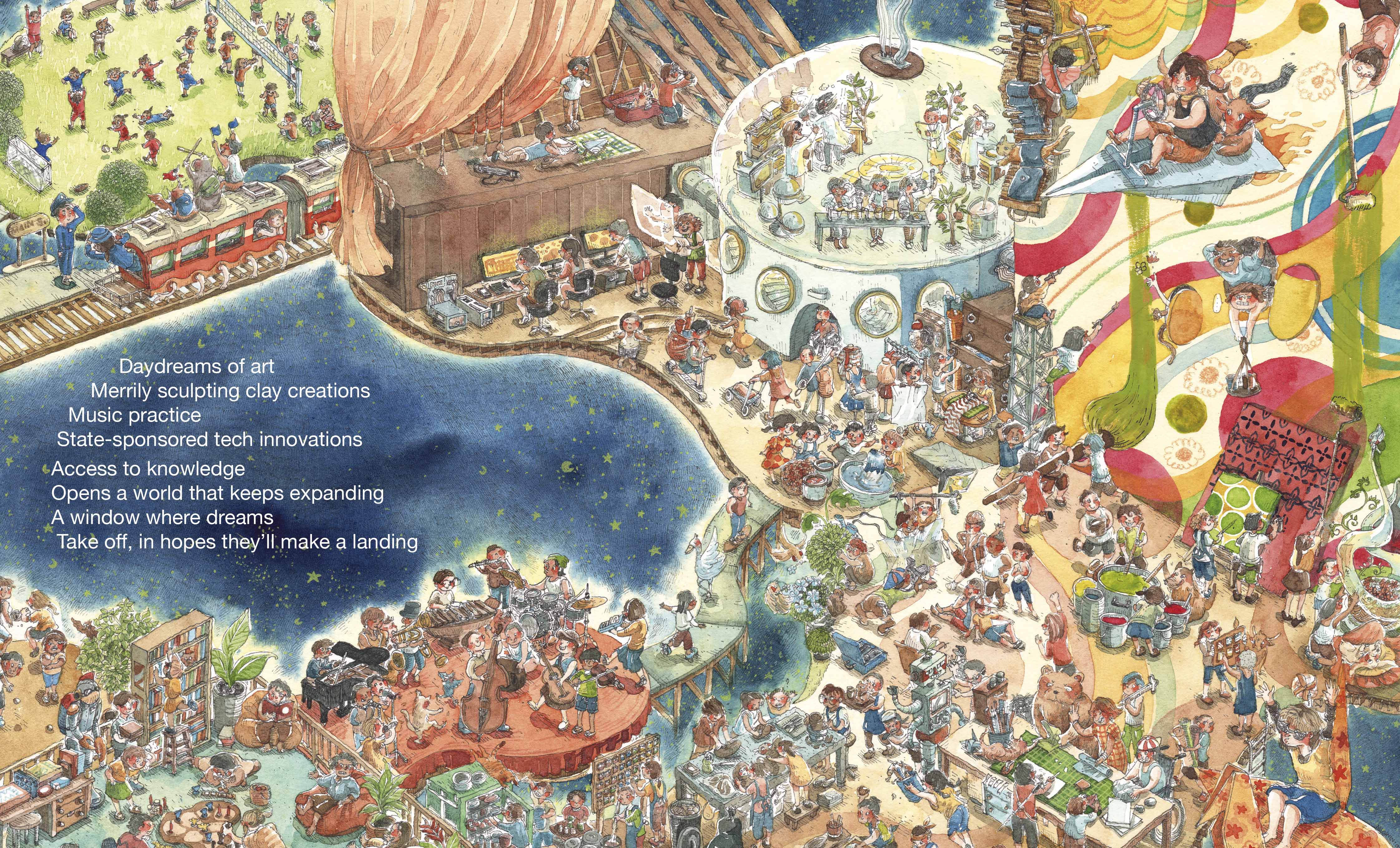

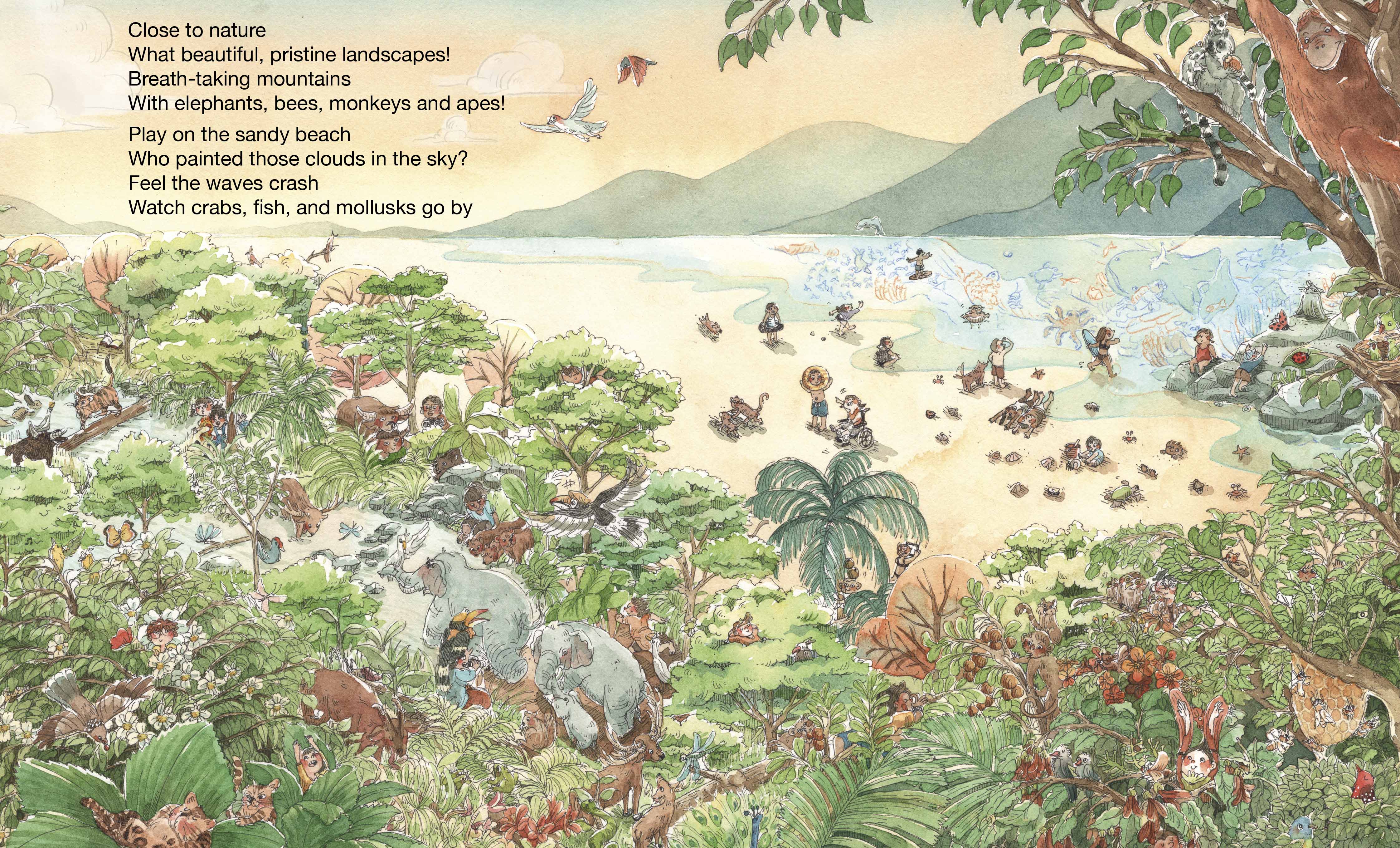

The curious child and the inquisitive parent rolled into one, the lone reader can mull over how the words illustrate the images just as much as the other way round. Each spread in Children Have Dreams is a panorama full of little characters up to something–a visual format evocative of the horizontal organization among the rank and file in the 2020 protests. The words, then, are like the speeches of an activist leader on stage. More often than not, one’s takeaway from participation in a protest has little to do with what one hears over the loudspeaker but a lot to do with the little things one observes around oneself. Similarly for a picture book: the part that actually sticks for children, according to psychiatrist and author Prasert Palitponganpim, is not the ideological content but rather the gap within and between words and images to be filled by speculation and imagination. Fittingly, an eight-year-old ends her review of this book, “Oh, also, I really like the drawings. They look real, and every corner has tales of its own.”