Written by Peera Songkünnatham

First published here on the eve of the 2026 Thai general election

[คลิกที่นี่เพื่ออ่าน “เดิงกีเก๋อ | อิจฉาเร๋อ” ฉบับแปลไทย]

“Milady is also having a hard time” (ying eng kaw lambak) was a catchphrase in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic era. The phrase came about in August 2021 from a Vogue Thailand interview of HRH Princess Sirivannavari and two other fashion designers. In her attempt to sympathize with people’s economic difficulties during covid lockdown, the princess’s quaint usage of thanying (‘milady’) as a first-person pronoun made her out-of-touch remark unintentionally hilarious, and thus memeworthy. The phrase’s satirical adoption was not only present in hashtags and TikTok clips but also plastered on people’s Facebook profile pictures.

Interestingly, Malaysia had her own royal faux pas in April of that same year, 2021, involving Tunku Azizah Aminah Maimunah Iskandariah, who was Queen at the time in the country’s rotating reign between nine monarchies. After Asia Sentinel reported that several Malaysian VIPs including the royal family had received the unapproved Sinopharm covid vaccine in the United Arab Emirates months earlier, Her Majesty’s followers on Instagram asked her about it. Under a post of dishes prepared by her and the kitchen crew, one follower asked if cooks at the palace had been vaccinated. The queen replied: “Dengki ke?” Or in slangy English, Jealous much?

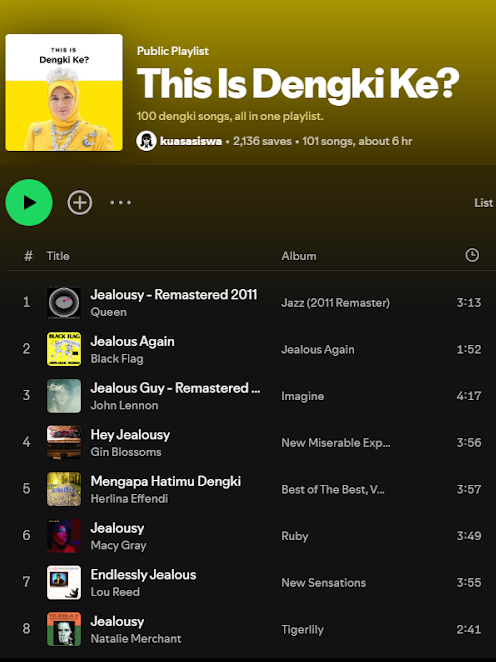

The Asia Sentinel report came out Saturday. On Monday, the queen deactivated her Instagram account. On Wednesday, a playlist titled “This Is Dengki Ke?” appeared on Spotify. Styled after the platform’s cookie-cutter playlists of an artist’s discography, the playlist features the queen on the cover art as if she were an artist named “Dengki Ke?” The playlist includes 101 songs with jealous or dengki in the title or in the lyrics, like “Mr. Brightside” by The Killers.

On Friday that same week, the playlist maker was arrested under the Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act for sharing “offensive and menacing content.” He was released on bail after being held for 24 hours (successfully negotiated down from 4 days by his lawyer—I’m jealous.)

Although the two royal remarks blew up in similar ways, they were opposites in intent. One meant to say “We’re all in this together” while the other probably meant to say “I don’t get why you’d have a problem if my people had VIP access to a vaccine,” which boils down to, “None of your business.” One claimed that people of all social classes were pierced by hardship; the other assumed that those who questioned the privileges reserved for her circle must have come from a place of misplaced ressentiment. (Apparently, dengki is stronger than jealousy.)

Of course, when you zoom out from the sentence level, you can see why the Thai princess’s remark was mocked. As a daughter of the richest monarch in the world, she was always going to be buoyed by her coffers, not to mention her little slice of the annual government budget. So to think that her hard time of being rocked by the pandemic and having to go without pay for three months to cover all her employees’ salaries was remotely comparable to the average citizen’s hardship was delusional. Ultimately, like the Malaysian queen, she was too self-absorbed in her circle of privilege to intuit or understand common[er] feelings.

Closing the current issue on outsiders, this essay thinks about envy and the outsider/insider dichotomy in Thailand and Malaysia.

The man who made the jealousy playlist was Fahmi Reza. This was not his first time clowning on someone in high office. In fact, he became widely known in 2015 for depicting then-prime minister Najib Razak as a clown. For that iconic depiction, he was sentenced to one month in prison and 30,000 ringgit in fines, although the sentence was later commuted and the fine reduced to 10,000 ringgit.

In Malaysian politics, the three inviolable topics are abbreviated as 3R: Race, Religion, Royalty. How awfully similar to the Thai motto (and Cambodian too) of Nation, Religion, King—down to the use of a mnemonic device: the Malaysian by alliteration, the Thai by rhyme: chāt, sāt-sanā, pra-mahā-kasat.

Fahmi Reza told me about the 3R during dinner by the Chao Phraya river in Old Bangkok. We were there in April 2024 for a workshop with about a dozen other democracy advocates from various Southeast Asian countries, mostly the Philippines and Malaysia. I was the only Thai at the table, so it was my pleasure to be the informant, both in the anthropological sense and the traitorous sense. Fahmi Reza already knew about Thai royalism from my presentations, if not from the news, but he was curious if any other institution in Thai society was also taboo to criticize.

My mind flipped through the institutions associated with nation and religion: the military, the police, the sangha. (I forgot about the libel-happy businesspeople and their irreproachable establishments.) Although some people faced a lot of persecution for insulting the military or the police, I said, the severity wasn’t really on the same level. And although Buddha statues were not to be trifled with, so many monks were on drugs or on gay hookup apps now, so fair game.

Looking across the river at Siriraj Hospital, I suddenly remembered the gigantic twin portraits of King Bhumibol and King Vajiralongkorn (placed inches below his father’s level) atop its centennial courtyard. I told Fahmi Reza, Well, even if only the monarchy is off-limits, the problem is the monarchy is in a lot of other things. Consider the covid vaccine: the king owns a drug manufacturing company, and the government decided to source the majority of the doses from this company. So can you criticize government policy on covid vaccines?

Later, looking around the table at my Malaysian friends, I delighted in sharing the enviable fact that the Thai parliament passed the same-sex marriage bill with actual support from political conservatives. Meanwhile, as I was soon told, Malaysian authorities had recently raided Swatch stores to seize watches inspired by the Pride flag.

My sense of national superiority was checked the following day. As I had presented about the breakdown of coalition building between the red camp and the orange camp after the 2023 general elections, one of my Malaysian friends followed up and asked how come the winning party became the opposition. She was not satisfied when I gave a mathematical explanation for the winner’s failure to form a government and the runner-up’s subsequent compromise with parties to the right. “But why?” she pressed. I did not realize we were talking about different levels of causation, and failed to go deeper. Her furrowed brow and tight-pursed lips must have had something to do with her country’s foundational history of coalitional calculations, of kicking some people out and sweeping other people in in the name of “racial balance”—a euphemism whose equivalent in my country may actually be “Thainess,” since authorities use it when they mean royalist supremacy. Can the people of our nations not get better things than sad compromises? that face seemed to demand. It occurs to me now that I must have sounded as glib to her as King Vajiralongkorn sounded to me when he said in an impromptu interview during the high point of monarchy-critical protest that “Thailand is the land of compromise.”

Because same-sex marriage did not pose a threat to royalist supremacy, its bipartisan passage was possible and perhaps even encouraged: a week after it became law, the king sent flowers and gifts to one of his servants who tied the knot with his boyfriend. I am not making this connection to be cynical; I am just realizing that legalizing same-sex marriage was useful for upholding Thainess.

A funny line of thought among younger Thais of Chinese descent these days is to lament our ancestors’ decision not to disembark before reaching Siam. We envy the prosperity of our southern neighbors, and fantasize about not having to be stuck in our royalist-militarist-extractivist dystopia. Why didn’t ah-kong and ah-ma migrate to Singapore or Malaysia instead?

One may shudder at the thought, considering the anti-Chinese riots of 1964 and 1969. But it is not so different, is it, from the way Thailand must appear to Malaysians who go to Hat Yai for a weekend of debauchery, or gaysians who go to Bangkok to be themselves—a fantasy of living differently in a place where the rules governing social behavior are more relaxed.

We want what we can’t have, and yet by indulging in superficial comparisons with our neighbors, we come to think about what kind of life we deserve to live and what kind of scenarios might take us there.

After learning of my plan to put together a Malaysia-inspired issue about outsiders, Fahmi Reza taught me the word pendatang. It means ‘one who arrives’ or ‘stranger’ and may refer to foreigners or migrants, but it also evolved to be a pejorative against Malaysians of Chinese or Indian descent. This usage of pendatang only makes sense in a dichotomy of sea sojourners and soil sons, where branding some citizens as perpetual foreigners will reinforce others’ status as insider natives.

Living under that zero-sum worldview, most people end up feeling like outsiders. In 2023, the nonprofit Architects of Diversity conducted a fairly representative survey of Malaysians with a sample size of 3,238 on the state of discrimination. Not only did they find that “the majority of Malaysians (64%) reported having experienced some form of discrimination in the past 12 months,” but they also discovered that “among major religious groups – Muslims, Christians, Buddhists and Hindus – each felt that members of their own groups experienced the most amount of discrimination.” The findings gained traction and appeared on the headlines of dozens of media outlets in Malay, Chinese, Tamil, and English.

(The most outsider religious group may, in fact, be the animists: most respondents “were unaware about discrimination relating to animists (beliefs of many indigenous groups), with 44% opting to respond with ‘don’t know.’ ”)

The outsider/insider dichotomy diminishes everyone. To immediately be a Malay Muslim in Malaysia, to use Zikri Rahman’s phrasing from the issue’s opening essay, comes with its own set of challenges. You cannot legally leave the religion as a Malay Muslim; the Federal Court ruled it impossible. In activist spaces, Fahmi Reza sometimes deliberately speaks English instead of Malay to fuck with people’s assumptions about him as a Malay Malaysian.

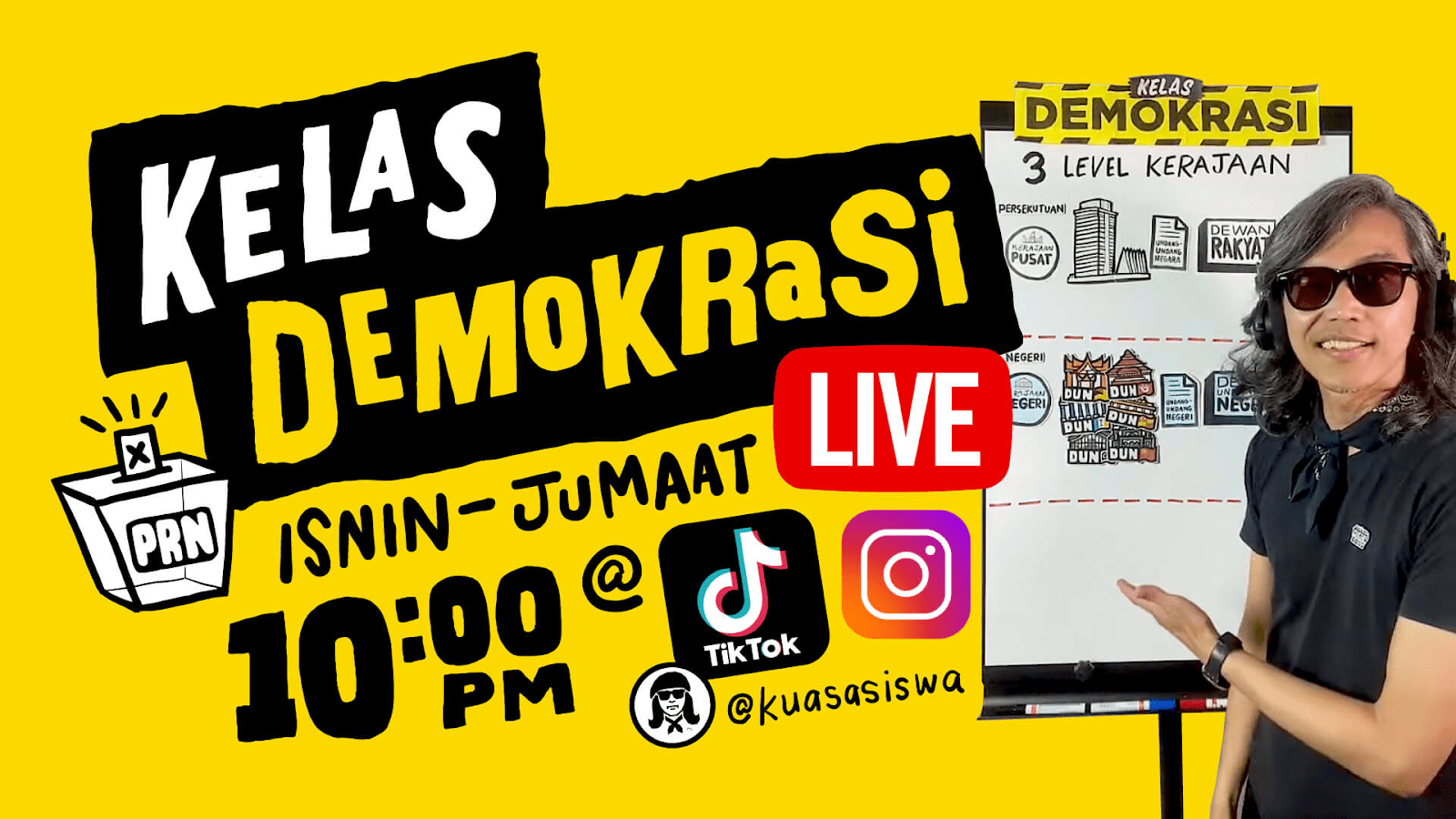

Trying to work around the dichotomy that governs not only one’s mainstream society but also the activist scene combating it, one might just arrive at an unexpected niche. Fahmi Reza’s most impressive accomplishment to me was not his satirical art, but rather his earnest initiative as a teacher. Parlaying his notoriety and design skills into a platform for nonpartisan political education called Kelas Demokrasi (Democracy Class), Fahmi Reza gave quick, digestible lessons about the country’s multi-level democratic system to youth and first time voters on TikTok and Instagram. University students began inviting him to give in-person classes, and all eight or so universities proceeded to ban or remove him from campus. He gave the classes anyway on the sidewalk or on livestream, hitting engagement numbers that would put any civil society campaigner to shame, or awe. And when TikTok cut his livestream and banned his account, he kept going. He has since trained a couple of youth cohorts who can run their own Democracy Class. (“It’s not branded,” he added during a presentation, “they don’t have to use my illustrations.”)

Looking up Fahmi Reza while writing this essay, I learned that he had been arrested again in December 2024 for insulting an incoming governor in the state of Sabah with another caricature. Fahmi Reza continues to do Fahmi Reza’s thing, and Malaysia continues to do Malaysia’s thing.

“Outsider is a good place to be,” a teacher told me long ago, when I was eighteen or nineteen. It sounded true to me then, but it occurs to me now that I didn’t truly understand it, because I proceeded to spend much of my twenties looking for belonging through activist collectives, mistaking fellow feeling outside the mainstream society for the ultimate good of outsiderhood. It’s like wanting your coworkers to be your best friends, I now realize to my chagrin. During the writing of this essay, I suddenly remembered the remark by Ms. O’Donnell from Existentialism class. I don’t remember what prompted her to say that to me; it’s possible I shared with her that I felt like an outsider at our prep school. (I didn’t realize she felt that way, too; looking her up, I learned that she had left and filed a lawsuit against the school for gender discrimination and retaliation for her advocacy on behalf of female students.)

Ms. O’Donnell said outsider is a good place—not thing—to be. Thinking of outsider as a place means it is not one’s given or acquired social identity, but a vantage point outside it that one ends up finding and finding uses for. Today, aged thirty-three, I actually feel my teacher’s remark to be true in my bones. I also have external evidence in the outsiders to the outsider/insider dichotomy whose good work I have internalized through translating and editing this issue of Sanam Ratsadon. Outsider is a good place to be.

One thought on “Dengki ke? | Jealous much? ”